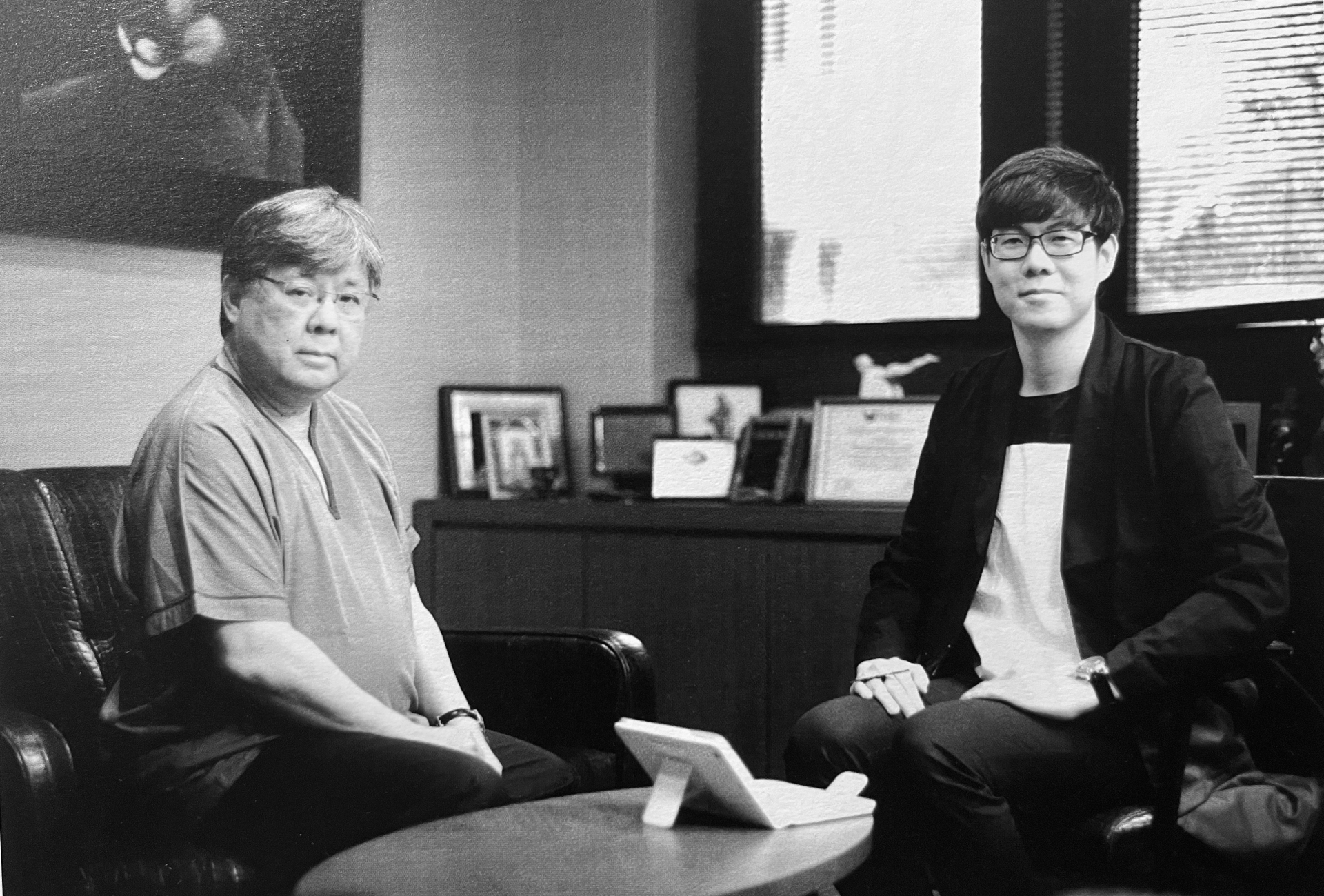

Revisiting a Timeless Conversation:

Originally published in 2015, this interview with Dato’ Dr. K.C. Tan offers profound insights into the state and future of healthcare, infrastructure planning, and the role of designers and architects in shaping medical environments. As we navigate new challenges and opportunities in healthcare design, Dr. Tan’s perspectives remain as relevant as ever. We’re excited to share this conversation again, inviting you to reflect on how far we’ve come—and where we’re headed.

Dato’ Dr. K.C. Tan is a name synonymous with excellence in the medical field. With over 400 liver transplant procedures to his credit and a trailblazer in pioneering medical advancements, Dr. Tan has earned widespread recognition for his contributions to medicine and life-saving initiatives. As the head of the Asian American Liver Centre at Gleneagles Hospital Singapore, Dr. Tan is a leading voice in healthcare innovation. In this interview, he shares his insights on the state and future of healthcare in Singapore and the region, the challenges of infrastructure planning, and the collaborative role of doctors and architects in shaping healthcare environments. Join us as we delve into the mind of a visionary—affectionately known as “The Liver Man.”

RC (CLQR)

Dr. Tan, I’m delighted to have you at our dialogue session. I’d like to start by asking about your views on the future of healthcare services in Singapore and around the region.

Dr. Tan

Singapore has all along been considered a medical hub and recognised for our strengths and developments in the medical tourism industry in this part of the world. But recently, countries such as Malaysia, Thailand, and India are beginning to recognise their own potential as medical tourism hubs with their governments supporting in their establishments. These are now catching up with Singapore. If you were to look at just the cost of medical procedures in these countries, they are now very competitive. However, Singapore still has an edge over them especially in procedures that require and demand advanced technology and sophistication and where profit margins are higher. For example, a simple procedure like removing the gallbladder can also be done in Chennai, New Delhi or Penang where the cost is significantly lower than that in Singapore. But more difficult procedures needing more sophisticated skills and advanced facilities, for instance, a liver or bone marrow transplant, they are better performed in Singapore. I would think that Singapore should move towards this direction rather than competing at the lower end of the market.

The other side of the equation is of course, the high concentration of specialists in Singapore. This is not by design but over the years, Singapore has opened its market for qualified doctors, regardless of nationality. For as long as the doctor is qualified, he/she is welcome to practise here. In countries such as Indonesia or Malaysia, it remains a ‘closed’ system to foreign doctors. As a result, in Gleneagles or Mt. Elizabeth Hospital in Singapore, you have many different eye specialists to choose from. We have specialists for the retina, glaucoma, anterior chamber of the ye, Lasik, etc. But in most of the hospitals in the regional countries, you will probably get 2 or 3 eye surgeons that will handle everything. As such, private medical practice is very competitive in Singapore and the doctors have to continue to hone their skills.

Countries like China or Vietnam are really quite far behind in terms of medical development. They have pockets of centre of medical excellence but the great majority of the people is still not served adequately. In the more popular medical centres in China, there could easily be 15,000 to 20,000 outpatients a day and cases can be misdiagnosed and as such mismanaged. That is why China has to open its doors to foreign doctors because they cannot cope with the present situation. The disparity is too great in the ratio of the number of doctors to the population. It will take a long time if they have to depend on their own doctors.

RC (CLQR)

What challenges and opportunities do you see when setting up medical infrastructure in less-developed countries?

Dr. Tan

Due to the ‘closed’ system, in many of the regional countries the foreign doctors often find it difficult working in this region. Often when a private hospital is set up in China or in Vietnam, it is difficult to attract doctors from the public institutions for various reasons. In Singapore, it is easier to attract skilled and experienced doctors form the public institutions to work in private hospitals. If China or Vietnam opens up in the near future to foreign doctors, it could be a different story.

I think the mindset of the patients is also a major factor. Patients tend to want to go to the top tier hospitals because that is where they know the famous professors are. Despite the long queues, they will continue to congregate there even if their contributions do need such expertise.

RC (CLQR)

How can the Asian American Medical Group (AAMG) contribute to providing medical services in these regions despite these obstacles?

Dr. Tan

For us, we felt that it would be beneficial to collaborate with a major medical institution in the USA to provide us with clinical oversight and support. In 2002 we have signed a service / collaboration agreement with The University of Pittsburgh Medical Centre (UPMC). The latter was at the time interested in expanding their services in Asia. This has enabled us to compete for contracts with insurance providers and national health authorities. The agreement allows us a springboard to go into China. We felt that to enter into their market, it will be good to invite a top western medical centre to provide additional support.

RC (CLQR)

How do you decide what medical infrastructure and technologies to introduce in these regions?

Dr. Tan

We make regular visits to the U.S. to see for ourselves what are some of the things that they can offer and would be of benefit to countries in Asia including Singapore and China. We cannot possibly import lock, stock and barrel from the western countries. In China, they will have their own medical systems such as acupuncture and TCM which are still useful. But over and above that, many Asian countries are not well-developed yet in technological advancements such as robotics, telemedicine, and telepathology. These are some technologies that we can bring over and offer to work with the local doctors.

RC (CLQR)

To implement these programs, what kind of a built environment do you think is ideal?

Dr. Tan

In all these programmes the core has to be good medical practice. Everything else – the spas, dietetics and meditation, etc., can then be built around it. This is where the architect will come in to design environments where the patients can feel comfortable while they are undergoing the treatment. After their chemotherapy or radiotherapy treatment, patients with cancer can rejuvenate their body by eating or resting properly in such environment.

RC (CLQR)

What about environments that can attract doctors, investors, and businesses?

Dr. Tan

Singapore has many advantages because it is both a transportation and financial hub. It is easy to come into Singapore because we are well-connected to the world. Secondly, if these doctors were to stay long term, say 2 to 3 years, they may want to arrange for their families to join them. The place should have appropriate schools and amenities that can cater for these families. China is a different ball game altogether because many of the cities are large enough to support the hospitals without the need for medical tourists. Thirdly, visa application for medical tourism in Singapore is one of the easiest to apply for.

RC (CLQR)

What do you see as the next big thing in healthcare services?

Dr. Tan

In the future, what the architects may be planning in support of these technologies will be what we call the ‘smart hospital’. For example, the minute you walk into the hospital, you could be registered by pupillary recognition. And no form is required to be filled. They will know who you are and your medical history. And therefore, these ‘smart hospitals’ will have to be designed by the architect.

I think the next big thing is going to be medical information technology. In the past, we would examine the patient and come up with a diagnosis. Today, we often put the patient through a scan, we have all the electronics to listen to the heart, to find out what is wrong. The skill of the doctor is thus slowly diluted and taken over by machinery. Similarly, an increasing number of our surgical procedures now depends on robotics. Our skill as a surgeon in a way has been negated. In more sophisticated centres in the U.S., a lot of planning and coordination are IT-driven. In telemedicine, we can now receive pathology slides, X-rays, and pictures/videos of patients in remote location where we can diagnose and treat.

“In the future, what the architects may be planning in support of these technologies will be what we call the ‘smart hospital’. For example, the minute you walk into the hospital, you could be registered by pupillary recognition. And no form is required to be filled. They will know who you are and your medical history. And therefore, these ‘smart hospitals’ will have to be designed by the architect.”

RC (CLQR)

Philosopher Michel Foucault wrote about the “medicalisation of the body”, where the patient’s body is no longer just the doctor’s concern but also the nation’s. What are your thoughts on this shift?

Dr. Tan

This shift is inevitable, especially with aging populations worldwide. Patient care can no longer be individualised; we must leverage technology to manage healthcare on a broader scale. For example, hospitals and nursing homes must be designed to address the needs of elderly patients with chronic illnesses, who often require long-term care and frequent readmissions.

RC (CLQR)

How can architects contribute to this evolving landscape?

Dr. Tan

If you look at advanced countries like in Japan, the U.S., or in England, there are many elderly communities such as retirement villages with all the appropriate amenities including medical care. The van comes in the morning and takes them to have their medical check-up, treatment, and exercises. These properties belong to the patients and when they passed on, the properties can be sold by the next of kin. Down the line, retirement villages will double up as medical care centres and hospitals will continue to be built. Such medical centres could become more common and are the places where the elderly with chronic diseases can be looked after and that’s where the architect will come in.

RC (CLQR)

Finally, how do you unwind outside of your medical practice?

Dr. Tan

My main hobby is thoroughbred racing, where every week I could be looking forward to a race in Japan or in Australia besides Singapore and Malaysia. In addition, I am also involved in breeding these animals.

Various things. I am very interested in the business side of medical practice and seeing the way it is shaping up in this part of the world allows me to think ahead of the curve. I want to be able to venture into places that people don’t often go such as Mongolia and Siberia. As a liver transplant surgeon, I have an advantage. Doctors, like architects, may find it difficult to go to other places to practice because of professional registration. But because I have a special skill in liver transplants, it is easier for me to get registered citing “technology transfer” as a reason. As private doctors, we have to continue informing ourselves and stay ahead of our competitors. People will catch up with you very fast and the best person is the one who remains paranoid, especially in business. You cannot remain static; to remain static in our profession means going backwards.

RC (CLQR)

Dr. Tan, thank you for sharing your invaluable insights. Your perspectives on healthcare, infrastructure, and the future of medicine have been truly enlightening and will surely shape the future of design and architecture in this regard. We deeply appreciate your time and wisdom.